SAX IN SPACE

Recently the Oxford American did an article about Ron McNair. Just search Oxford American Ron McNair.

This article below was written in 1986 for NASA - North American Saxophone Association magazine.

The saxophone became the first musical instrument in history to be played in outer space.

(There had been a tiny harmonica and jingle bells on a previous mission. ) Then tragedy took away its newest pioneer.

By Kurt Heisig (1986)

For over two years I've waited to share this story about astronaut Dr. Ron E. McNair and his contribution to the history of the saxophone.

In August of 1983 I was summoned to the phone to answer some questions for a caller about the difference between straight and curved soprano saxophones. The caller seemed to be another typical Silicon Valley type and I enjoyed the conversation, but I didn't realize this was the beginning of a great adventure.

A short time later I received another long distance call from the same fellow. He was still trying to decide which form of the saxophone he wanted. He had originally wanted a straight soprano, but now he had a definite preference for the curved one. He was a very intense man and there seemed to be other factors on his mind that were influencing his decision rather strongly. He asked me to rent a soprano to him! I tried suggesting different alternatives to help him, but he still wanted to rent. He was a likable fellow, and so sincere that I really wanted to help him. The problem was that he was in Texas, three states away. There was a bit of silence on the line as we both tried to find a way to make this work. Then he said, "You see, I'm an astronaut and I wanted to take it on the space shuttle with me."

Well, in all these years I've heard some good lines, but this was pretty incredible! Suppose he was an astronaut? As it turned out, he was an astronaut! I helped him to rent a saxophone.

Ron was tenor player, but he was hoping to get permission to take a saxophone with him on his first space shuttle flight and only the soprano would fit. He preferred to rent an instrument until he received final permission to take it. It turned out that the decision about curved versus straight soprano saxophones was made for Ron McNair. The astronauts' personal stowage is an inch and one-half too short for a straight soprano in B-flat.

Ron had just a few short months to get his soprano playing up. In order to prepare as quickly as possible. I helped him -- by telephone! He had a Ph.D. in physics and I had done research in acoustics, so the idea wasn't as far fetched as it might sound. Over those months at about any hour, the phone would ring. I'd hear "Hey Koit!" in that melodious voice of his, and we'd get down to the problem at hand.

At times, his calls would come while I was teaching a lesson, and I'd point to a chair and signal for my students to listen. Since Ron did not yet have final permissions and did not want to jeopardize his chances of taking a saxophone with him on the shuttle, it was important that there be no advance publicity of the event. I would couch my terms and merely inform my students to pay lots of attention; that this might be a piece of saxophone history in the making.

The first big hurdle was for Ron to prepare for the possibility of playing at low cabin pressure. Many of us Bay - area musicians have had to play one day here at sea level and then drive to Tahoe and play at 5,000 feet, only to discover that a previously playable reed now felt like a plank! To address the pressure problem, Ron worked on exercises that had been developed by the late clarinetist, Clarence Warmelin (low B-flat, B, B-flat: Bflat, C, B-flat, etc.) always slurring, using the syllable "augh", and blowing stronger with each note change. He also worked to use lots of air so that he could move up in reed strength as soon as possible. We wanted to work him up to Vandoren #5 reeds for the best results.

Ron became comfortable on strong reeds in a very short time. This proved to be a real advantage because it turned out that the shuttle cabin pressure was kept low at times. He also had a few softer reeds to fall back on. Later, to my surprise, he told me that he had used the hard teeds when playing even in low cabin pressure.

It was a fascinating challenge to help him by phone. I'd explain a concept like movement of the fulcrum point on the reed or how biting will cause severe problems, and then he'd go back to practice in the little time an astronaut gets to himself. It was amazing how quickly Ron mastered things and moved on. It was a tremendous joy to work with him.

Word came through at the last moment tht Ron would be allowed to take his saxophone aboard the Challenger shuttle. Needless to say, I told my students to watch the news for a saxophone event, though I still couldn't tell anyone why!

The space shuttle Challenger lifted off from Florida on February 2, 1984. Over the duration of the flight, I don't think I missed a single hourly news broadcast. The last word from Ron was that he was sure the saxophone had been cleared, and that he would play it in space. Days went by, and there was a still no news of the event.

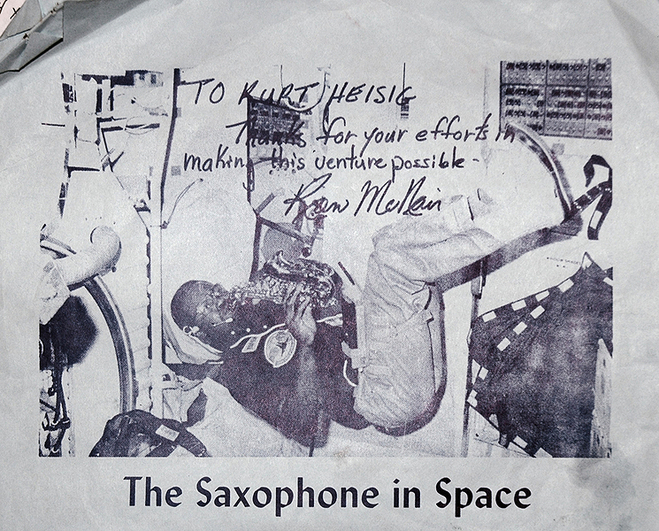

The shuttle landed safely on February 11, 1984. About a week later after Ron returned to Houston I wired him: "Did you get to take it? Use it? How did it go?" When I finally reached him, he told me that he had gotten to play the saxophone in space! For some reason, there had been a press blackout. Later, though, there was a press release about the event and mention was made in a few scientific journals., Aviation Week & Space Technology among them, that the event had indeed occurred. A picture of Ron floating in the shuttle and playing the saxophone was released by NASA.

At that point Ron sent me some pictures, including one of him playing the saxophone in space, and he told me that his project was not yet completed. He wrote to me, "We must remember, since you are now up to your chin in ths, that the project is not yet completed. Having a picture of a sax in space and having the world hear one being played from space are two entirely different events with as different impacts. "

Ron and I discussed the problems he had in playing the saxophone in space. The sound was normal. The cabin pressure was kept low, but thanks to his practice he was able to play on the heavy reeds. Then there were problems with lack of gravity, and these proved particularly interesting.

When a wind instrument is played, the moisture collects and runs down, but in zero gravity there is no "down." Evidently, molecular attraction becomes a real problem after 15 minutes or so of playing in zero gravity. Lacking a "down," the water molecules collect to form water balls that eventually lodge in a tone hole and a bubbling sound is produced. Ron coined this the "bubble effect."

A problem with the pads was one that took us both by complete surprise. The air in the shuttle is very thoroughly filtered and dry. When Ron first took his saxophone from the plastic wrapping material, it played fine. When he left it out awhile, it played poorly until he had played for another 15 minutes, then it would recover. If he then wrapped it in the plastic packing material, it would play fine right away when taken out again. Ron was certain that the dry air had this effect on the pads.

In April 1984 I finally met Ron for the first time face to face when he stopped here for a visit, and I got to check the instrument. It was in perfect condition. I remarked that I was surprised it could play at all after the tremendous vibration it went through. At the mention of vibration Ron's face lit up. He described the ride with great excitement and he told us that the power and vibration ot the ship were absolutely incredible.

We were all excited that this extraordinary deed had been accomplished by such an exceptional man. The first musical instrument in space had been a saxophone!

We thought back over the chain of events. There were the initial inquiries about the instrument. Then, Ron worked for months for permission to take it with him aboard the shuttle. My help had come by phone, and it was literally crammed in by both of us. It had been a hectic period, and Ron was working unbelievable hours. Ron made such great efforts to develop his soprano playing in a short time, and in the end there had been no news. He told me that he had at least made a tape. Misfortune struck again, for the tape had been accidentally erased.

Ron and I often discussed how the saxophone was the brunt of so much bad luck and prejudice. Ron had seen that the saxophone attained historical status as the first musical instrument to be played in space, but no one on the ground had a chance to hear it. We were so happy, yet so frustrated. Everyone wanted to hear him play from space next time

... next time!

We told only a few saxophonists, music students, and teachers. Playing the saxophone in space was still a semi-private project. As Ron would say, it was a "fact" that this had been accomplished already, but he still hoped to be heard playing on a broadcast from space, so we tried to keep publicity to a minimum and wait for the next time.

One day in early January 1986 the phone rang. It was was Ron: he was flying again, but permission to take saxophone did not look good. Could I send him some more Vandoren #5 reeds?

The first time in space, Ron played a medley of three songs, two of which he played over the phone for me to see how they would sound with less than ideal transmission. I believe that one of those songs was America.

Trying to find an idea that would get the saxophone aboard this time, we discussed the educational aspects, the idea of playing Happy Birthday for the President (but Ron would have been back from space by Feb. 6), and any other ideas that might win a place for the saxophone on the shuttle mission. Ron thought he had an idea that looked promising, and he said he'd call me back.

A week later he called from quarantine, " Hey Koit!" He was practising a few hours every day. Where were those good reeds I'd promised? There was a chance to get the saxophone aboard the shuttle. Texas was having a sesquicentennial celebration and NASA, of course, was a large part of Houston's history. The composer Jean Michel Jarre was writing some music, and Ron called with some questions. Ron was a jazz player, and this was interpretation by telephone of brand new music. It looked like the saxophone would finally be heard from space.

We began problem-solving for the "bubble effect"" and the dry pads. For the pads, I suggested folding a plastic bag inside the bell, and if the saxophone acted up in the dry, self-contained atmosphere, he could create his own humidity swamp by putting the saxophone in the bag, blowing it up, and tying it off. Ron felt that the plastic wrapping material would provide the same remedy.

For the "bubble effect," I suggested that he take the mouthpiece off periodically, finger low B-flat, and blow through the tube with force to expel the water balls. It was agreed that would work well. (previously, we talked about a standard weighted swab. Weighted? .... oops.)

On January 28 I missed seeing the launch on television due to a bout with the flu. Several people tried to phone me, and finally one of them reached me: "Did you hear about the shuttle?" In my fever, I thought there had been another delay. Then I heard the tragic news.

Since that time, I've thought about all the fun I had working with Ron, and about his infectious enthusiasm. Still, I half expect the phone to ring and hear, "Hey Koit!" I also remember how badly Ron wanted to share this event with the world: the saxophone, live from space.

When things settled down a little, I checked with a secretary at NASA and was told that the saxophone had not been on board the shuttle. Other sources indicate that the instrument was indeed aboard. Ron went into space with his Grover Washington Jr. tapes to relax by, and with the hope that he could play his own saxophone for the world to hear.

Ronald McNair was a unique person: a respected physicist, a NASA astronaut, and an avid saxophonist. The tragic event on January 28 will not be soon forgotten. But one of the men aboard was someone who should be remembered by musicians and especially by saxophonists, for on his previous space mission, Ronald McNair had become the first man to play an instrument in outer space - the saxophone.